- Home

- Scarrows

- Mariners

- Cumberland

- Miscellaneous

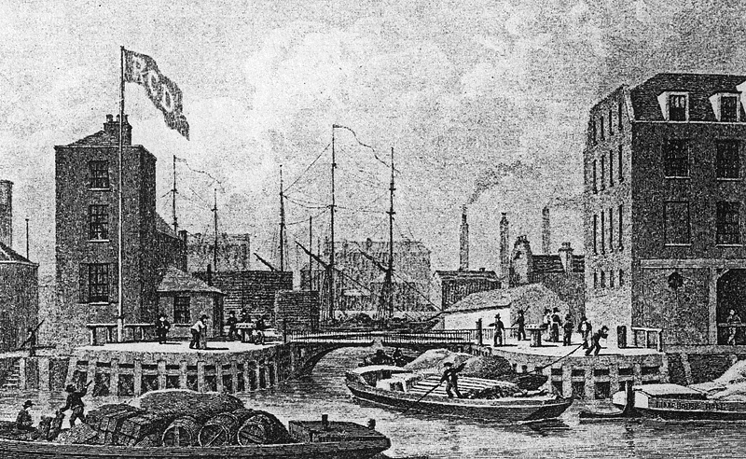

London, Limehouse and Poplar

London, Thames, circa 1840

The outpost which would become London first appears in history as a small military storage depot employed by the Romans during their invasion of Britain, which began in A.D. 43. It was ideally located as a trading center with the continent and soon developed into an important port. It had already become the headquarters of the Procurator, the official in charge of the finances of Roman Britain, when Boudica, the Queen of the Iceni, a native British tribe inhabiting East Anglia, burnt it to the ground in A.D. 61 in the course of her bloody revolt against Roman rule. It was rebuilt by the year 100, and first appears as "Londinium" in Tacitus's Annals. It rapidly became both the provincial capital and the administrative, commercial, and financial center of Roman Britain. Its population by the middle of the third century numbered perhaps 30,000 people, a number which grew in fifty years to nearly twice that number. They lived in a city with paved streets, temples, public baths, offices, shops, brick-fields, potteries, glass-works, modest homes and elaborate villas, surrounded by three miles of stone walls (portions of which still remain) which were eight feet thick at their base and up to twenty feet in height.

During the course of the fourth century, however, as the Roman Empire began to collapse, Roman Londinium fell into obscurity as its protective Legions withdrew; history records no trace of it between 457 and 600. During that time, however, it gradually became a Saxon trading town, eventually one of considerable size. In the same century Christianity was introduced to the city (St. Augustine appointed a bishop, and a cathedral was built), but the inhabitants resisted and eventually drove the bishop from the city. It was sacked and burned by the Danes in the ninth century, but was resettled by Alfred in 883, when the Danes were driven out, the city walls were rebuilt, a citizen army was established, and Ethelred, Alfred's son-in-law, was appointed governor. It continued to grow steadily thereafter, though because most of its buildings were constructed of wood, large fires took place with unsettling regularity.

Lunduntown (as it was now called) retained its preeminence after the Norman Conquest, which began in 1066. Though William the Conqueror had himself crowned at Westminster Abbey, he distrusted the Saxon populace of the city, and constructed a number of fortresses within the city walls, including still extant portions of Westminster Hall and the Tower of London. In 1176 work began on a new stone bridge to replace the wooden one which the Romans had built a thousand years before. The new bridge (which, in its turn, acquired the name of Old London Bridge) was completed in 1209, and would be in existence until 1832, remaining the only bridge across the Thames until 1750.

London bridges, Thames, circa 1840

The city became a true capital under Edward III, who placed the royal administrative center at Westminster during his reign in the fourteenth century. London was the only British city in mediaeval times which was comparable in size to the great cities of Europe. Between 1500 and 1800 it grew steadily in size and prominence, though during the middle ages its population never reached the levels it had attained in Roman times. Its population increased, however, from perhaps 50,000 in 1500, to 300,000 in 1700, 750,000 when George II assumed the throne in 1760, and 900,000 in 1800, in spite of living conditions which, over the centuries, were so unhealthy that the rapid increase in population could be sustained, in the face of an enormously high death rate, only by a steady influx of immigrants from other parts of Britain. [The death rate in the city, well into the eighteenth century, was twice the birth rate. The average life span of an Englishman, during the early eighteenth century, was 29 years, and in London the average was considerably lower.] The streets, since medieval times, had always been filthy, filled with mud, excrement, and offal; the water was polluted, rats were omnipresent. The Black Death of 1348-49 killed two-thirds of the inhabitants of the city proper and its surrounding areas (at least 60,000 people), and there were three subsequent serious outbreaks of the bubonic plague between 1603 and 1636, but the city (and the slums) continued to increase in size. The last major outbreak of the plague occurred in 1665; during the summer of that year perhaps 70,000 persons died. There were large-scale outbreaks of cholera in London proper well into the nineteenth century.

The urbanization of London continued and intensified during the Industrial Revolution, and on through the nineteenth century. From the middle ages on, and well into the nineteenth century, much of London was violent and squalid. During the eighteenth century, the poor and the unemployed frequently occupied themselves, as Hogarth demonstrated, by drinking themselves into insensibility; one doctor reported that one of every eight Londoners drank themselves to death. In 1742 London had one gin-shop for every seventy-five inhabitants. During the 1740s the English consumed 7 million gallons of gin, as opposed to 1 million gallons during the 1780s, when it was heavily taxed.

London epitomized the process of social stratification which took place in Great Britain. As the city grew in size, the poor became increasingly crowded into the filthy slums in the eastern part of the city while the merchant and the professional classes and the gentry established themselves in the fashionable suburbs in the west. The Gordon Riots of 1780, for example, were ostensibly motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment, but were a manifestation of the deep hostility which the poor felt for the wealthy. Homes were attacked, looted, and burned, Newgate and Fleet Prisons were attacked and their prisoners released, and troops were required to restore order.

By 1750 one tenth of the population of England resided in London, and it was the undisputed cultural, economic, religious, educational, and political center of the nation. Population growth continued unabated through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. By the time Dickens died in 1871 the population of London was well over 3,000,000, and the spread of the prosperous middle classes into suburban areas surrounding the city proper was well underway. Less than a century later, the population of metropolitan London would be over 8,000,000.

London was, of course, also Britain's artistic and literary capital. For centuries, with its publishers, newspapers, journals and weeklies, Coffee-Houses, taverns, and literary salons, the city played an important (and frequently crucial) role in the life, development, and work of virtually every English literary figure of any significance. Hogarth and Rowlandson portrayed it in their work as the great eighteenth-century authors did in theirs.

Port

Limehouse, 1828

London has been a port since Roman times. It became an important trading city because of its links to the rest of the country over land and to the rest of the world through the river Thames. Roman galleys moored along the river trading a range of goods from around the Roman Empire. London continued to grow when the Romans left and the river became very busy.

During the time of Queen Elizabeth the First, the river became so crowded that there was sometimes nowhere for ships to unload and they had to put their cargo onto smaller boats, which would go to other parts of the river. The overcrowding also meant that goods were often stolen. Laws were passed to control where ships could legally moor and for how long they could stay. The situation became much worse as ships became bigger and London grew as a trading city. Something had to be done.

In the early nineteenth century, companies such as the West India Company began to build docks to allow their ships to moor next to their own warehouses. These were very successful and other companies quickly built new docks such as the London docks and the East India docks.

Each time new docks were built, trade increased and these docks all seemed too small. At this time, England was producing a huge range of goods in newly built factories. This period is known as the industrial revolution. The goods made in these factories were sold all over the world. They had to be shipped through ports such as London. At the same time, The British Empire grew and other goods came to London from around the world. Very soon, the docks could not cope. The decision was made to build new docks further downstream. These were the Royal Docks, which started with the Royal Victoria dock, which was opened in 1855. The Royal Albert dock was finished in 1880. The last of the Royal Docks to be built was the King George the fifth dock, opened in 1921.

Regents Canal Dock, 1828

Many thousands of people worked in the docks. They loaded, moved and unloaded the huge quantities of goods traded through the docks. Most things had to be moved several times. First, from the boat to barrows or trucks. They were then put in warehouses, packed and put on lorries or trains to be moved again. Dock work was poorly paid and often dangerous.

Imports

| Goods | Place of Origin |

|---|---|

| Cotton | U.S.A. |

| Sugar | West Indies |

| Spices | India |

| Tobacco | Virginia |

| Timber | Canada |

Exports

| Goods | Destination |

|---|---|

| Manufactured Goods | Worldwide |

Industry

| Port Industries | Other Industries |

|---|---|

| Shipbuilding | Banking |

| Ship Repairs | Government |

Scarrow Associations

Along with Harrington, Whitehaven, Workington and Liverpool; London was one of the (five) ports in which one or more of the Scarrow mariners was based. Towards the end of the careers of Joseph and Thomas, many of the voyages involved a call to the port of London. Throughout Robert Barnes Scarrow's career, either London or Liverpool, was the point of departure or arrival. Joseph Scarrow had an abode here at 6 Old Road, Stepney, and Thomas had an abode on Great Hermitage Street.

| Scarrow | Period |

|---|---|

| Joseph Scarrow | 1849, 1851-1853, 1855-1856, 1862-1863 |

| William Scarrow | 1849, 1852-53 |

| Thomas Scarrow | 1865-1871. Residence from 1871 until his death. |

| Robert Scarrow | 1906-1907, 1918, 1921-22, 1925, 1927-29, 1931 |